project willshake

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please.

—William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Epilogue

1 prologue

The Tempest was one of Shakespeare’s last plays. At its center is an old man named Prospero who is always talking about his “art”—meaning the magic powers by which he weaves the actions of the plot, controlling spirits and men and even the elements of nature. He learned this art, he explains, from studying books, even to the neglect of his own life. Finally, having used his powers to achieve all his earthly ends, he ceremoniously retires his “charms,” frees his spirit-servant, and turning to the audience, pleads for his own freedom from the “bare island” where he has been “confined.” It’s impossible not to see Prospero as a virtual Shakespeare and The Tempest as the playwright’s valediction to the stage. In the epilogue, Prospero is clearly not just talking about the events of the day, nor of The Tempest itself, but of all the author’s work when he says his “project… was to please.”

This document lays the foundation of project “willshake,” which takes up Shakespeare’s stated wish to please—not on stage, where he knew that the “gentle breath” of actors would carry his words, but in the “insubstantial” world of the web, “the great globe itself.” In this “brave new” otherworld of pure signals, where music, words, and art fly round the earth like spirits, Shakespeare, and others who complete their “service,” may be in a new sense set free.

2 mission

Project “willshake” is an ongoing effort to bring the beauty and pleasure of Shakespeare to new media.

2.1 vision

I want a place that:

- puts Shakespeare’s actual works front and center

- presents the plays as entertainments, for recreation

- is built to last, meaning to be rebuilt

- is beautiful. curated for high-signal and low-noise.

- never publish unreviewed material from any source.

- never show ads or other irrelevant distractions

- is designed for humans

- rational and emotional

- a pleasure to use, opening the mind and heart

- is free for everyone

- is legal (sources all content and respects copyright)

At the same time, I recognize that willshake is not

- a community project. The royal “we” is just an old programmer’s habit. This is my domain.

- a temple to Shakespeare. The less mediation the better. But see previous point.

- a scholarly resource. Like Shakespeare’s own works, willshake is intended for a general audience. Shakespeare scholarship has its own world of resources, that are of interest mainly to itself.

- a newsroom. “There’s no new news… but the old news.” (As You Like It)

2.2 prior art

For what willshake undertakes (starting with the above objectives), there is no prior art. If you find anything in the world that does or attempts to do the same thing, please reach out at your earliest convenience.

Of course, there are countless Shakespeare resources in all existing media, and as I illustrate in a moment, there have been similar efforts for older definitions of “new media.” Some of the other documents in the project do touch on prior efforts in specific areas.

3 rationale

Reynaldo: But, my good lord,—

Polonius: Wherefore should you do this?

Reynaldo: Ay, that I would know.

Hamlet

Willshake is essentially an art project, and a labor of love. It would seem odd to ask a painter what is the “rationale” for a painting, or a singer the “rationale” for a song.

But willshake is also a software project. And the idea of a software project without a clear rationale makes me squeamish. So here it is.

3.1 why Shakespeare

How can we maintain excitement, interest, and aesthetic pleasure for a lifetime? I suspect that part of the answer will come from the study of those things that do stand the test of time, such as some music, literature, and art.

—Don Norman, Emotional Design

I’m not here to convince anyone that Shakespeare is good. If you don’t like Shakespeare, so be it, “for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” As Heminge and Condell say in their address “To the great Variety of Readers,” “it is not our province, who only gather his work… to praise him. It is yours that read him.” For my part, I am sure there are a thousand lines we could live without.

But I will say this: Shakespeare is the “king of all media,” if there ever was one.

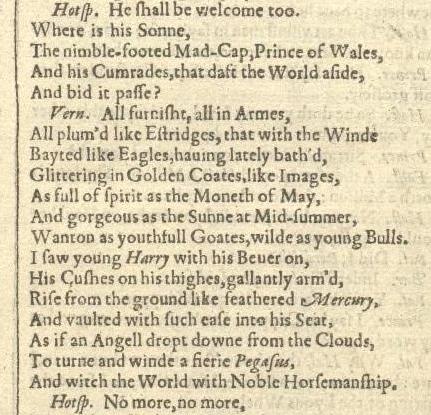

Obviously, Shakespeare is the reigning champion of the stage drama. But the playwright has also lived a parallel life in print, which has been just as strong as his stage presence. By the time London’s theaters were banned in 1642, his complete dramatic works (an expensive book) was already in its second edition—notwithstanding that the King’s Men had sought to prevent the publication of the plays during his lifetime. Today, we have his works in all languages, and in every unpreventable variation one can think of.

Shakespeare’s ubiquity is indeed not limited to art forms or media that existed in Elizabethan England. He probably never heard an opera in his life, yet it was the irresistible appeal of a Shakespeare project that drew Giuseppe Verdi out of retirement in the late 1800’s to create his influential masterpieces Otello and Falstaff. Sixty years later, West Side Story likewise marked “a bold new kind of musical theatre.”1 In film, a short scene of Hamlet made in 1900 serves as “one of the first examples of sound and moving image-syncing,” and by 1999 the Guiness Book of Records had found Shakespeare to be “the most filmed author ever in any language”—not bad for a guy who died hundreds of years before the invention of movie cameras.2

If you’re exploring the possibilities of a new medium, you have two choices: you can create material from scratch, or you can adapt existing material. Orson Welles—perhaps the next contender for the title “king of all media”—wisely did both, producing numerous Shakespeare plays for Broadway, film, and radio. His Columbia Shakespeare series, made in the late 1930’s with a group of world-class actors, shows his particular gift for the radio and has held up very well.3

However, there’s a risk that, in adapting “old” material, you will not exploit the full potential of the new medium. For the “dynamic” medium that is now emerging—unlike any before it—such shortfalls are inevitable. This was the case in 1993 with shakespeare.mit.edu, one of the first web sites ever made. Even then it was little more than a plain text, and it has not changed since. Yet it remains popular, since nothing decidedly better has come along.4 I will return to the “dynamic medium” shortly.

Shakespeare’s plays are both timeless and formless. They are an essence that can fill any space, any undiscovered setting. They are pure human expression: people speaking for themselves, and singing, and loving and dying. They are distilled thought and feeling and action. Any medium worth having must be good for at least that much.

3.2 why beauty and pleasure

Beauty is bought by judgement of the eye

Loves Labour’s Lost

If you’re not having fun, you’re done.

KRS-One

I don’t know when it happened, but at some point Shakespeare went from being “good” to being “good for you,” thus joining the ranks of homework and vegetables and jury duty. “Shakespeare” has been institutionalized—and even worse, he’s systematically introduced to people when their view of institutions is at its lowest. It was no different for me.

According to Samuel Johnson, “Nothing can please many, and please long, but just representations of general nature.” Leaving aside his main point, notice the focus on pleasing people. Surprisingly enough, this issue—the pleasing of people—concerned the great literary critic. In 1765, Dr. Johnson declared that Shakespeare, being dead for more than a century, no longer enjoyed any “personal” advantages and that

his works… are read without any other reason than the desire of pleasure, and are therefore praised only as pleasure is obtained.5

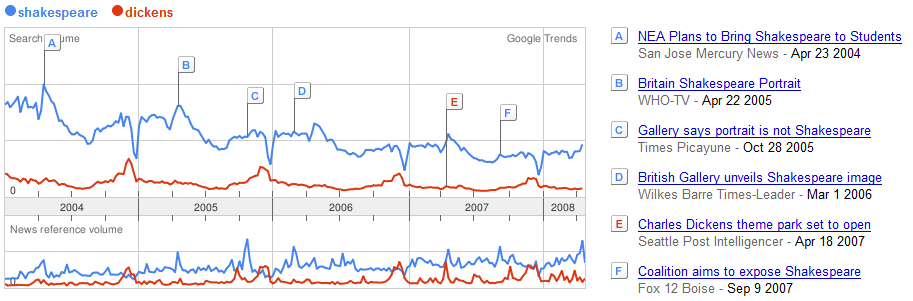

This hedonistic view may sound strange now, at a time when many people’s experience of Shakespeare (and literature generally) is confined to the standard school curriculum. Consider Figure 2, which shows the Google search trends for the terms “shakespeare” and “dickens” over the span of several years.

Ignoring for the moment the overall decline, there are two annual rhythms at play: the nine-month school year and the performance season. Interest in Shakespeare—at least on Google—is highest in the spring, when English classes start to overlap with the theatrical calendar. I assume it is the “summer Shakespeare” tradition that keeps attention from dropping off completely during vacation. But in general, it looks to me like school is the sustainer here—students searching for help with assignments. Interest sharply drops off during winter break (when Dickens gets his Christmas bump).

Willshake’s mission is to assume that people are visiting “without any other reason than the desire of pleasure.” There is no ambition to be an “educational tool.” But even if willshake were meant to be some kind of study guide, I’d take the exact same view.

Pleasure does not conflict with study—on the contrary, poetry and drama must please before they can instruct. Shakespeare takes up this argument in Love’s Labours’ Lost, a “comedy” in which four men vow to study for three years’ time, abstaining from practically every pleasure of life. But before signing his name, Biron (the star of the play) protests some of these conditions as too “strict,” including “not to see a woman.” He argues (in rather convoluted terms) that this “barren” approach must fail—that the “pain” of study undermines its very aim,

As, painfully to pore upon a book

To seek the light of truth; while truth the while

Doth falsely blind the eyesight of his look.

Instead, he says,

Study me how to please the eye indeed

By fixing it upon a fairer eye,

Who dazzling so, that eye shall be his heed

And give him light that it was blinded by.

The sight of a beautiful woman, he insists, will do more for his wit than any book. More generally, as the cognitive scientist Don Norman puts it, “emotion makes you smart.” And the quality of the feeling matters: “positive emotions are critical to learning,” whereas “when people are anxious, they tend to narrow their thought processes.” It’s all the more shame, then, that the very name of our greatest comic genius conjures up negative emotions in so many people. Witness the popularity of study programs such as “No Fear Shakespeare” and “No Sweat Shakespeare.”6 Maybe these resources help serve the mutual ends of making money and passing classes. But for the purpose of feeling why we should care in the first place, they’re doomed from the start.

Beauty and pleasure—or, taken together, aesthetic pleasure—must be seen as the entryway to intellectual and moral thinking; not the other way around. For an illustration of this, we turn to a great detractor of Shakespeare’s: Leo Tolstoy. Inspired by Ernest Crosby’s article “Shakespeare’s Attitude to the Working Classes,” Tolstoy wrote his own essay along similar lines, ultimately an argument calling for a revival of religious drama and criticizing what he saw as Shakespeare’s moral irresponsibility. But see in the following passage how Tolstoy describes his experience of the works (emphasis added):

I remember the astonishment I felt when I first read Shakespeare. I expected to receive a powerful esthetic pleasure, but having read, one after the other, works regarded as his best: “King Lear,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Hamlet” and “Macbeth,” not only did I feel no delight, but I felt an irresistible repulsion and tedium, and doubted as to whether I was senseless in feeling works regarded as the summit of perfection by the whole of the civilized world to be trivial and positively bad, or whether the significance which this civilized world attributes to the works of Shakespeare was itself senseless. My consternation was increased by the fact that I always keenly felt the beauties of poetry in every form; then why should artistic works recognized by the whole world as those of a genius,—the works of Shakespeare,—not only fail to please me, but be disagreeable to me? … I have, as an old man of seventy-five, again read the whole of Shakespeare… and I have felt, with even greater force, the same feelings,—this time, however, not of bewilderment, but of firm, indubitable conviction that the unquestionable glory of a great genius which Shakespeare enjoys, and which compels writers of our time to imitate him and readers and spectators to discover in him non-existent merits,—thereby distorting their esthetic and ethical understanding,—is a great evil, as is every untruth.

For Tolstoy, what is first experienced as beauty and pleasure—or their lack—ultimately develops into “conviction” and “ethical understanding.”

3.3 why new media

Whatever we did to deserve it, we are living in very interesting times. There can be no doubt that the development of computing technology (what Bret Victor calls “the dynamic medium”) marks a change in the course of humanity far more profound than that of the printing press—maybe even rivaling language itself. If, as Alan Kay observes, the true impact of Gutenberg’s invention took hundreds of years to reach the general public, where does that leave us now? All we can say for sure is that no one knows where the story goes from here. With any luck, we’ll live long enough to be blindsided again.7

In his 2014 presentation “The Humane Representation of Thought,” the luminary and polymath Bret Victor considers our stake in the direction of this new medium as a moral question, but also a practical one: it’s both inhumane and inefficient to “cage” ourselves in devices that recognize only a small fraction—a mere trickle—of our rich human capabilities. In particular, he decries the nearly exclusive emphasis on visual and symbolic channels (necessitated by small, rigid screens), at the expense of all our other high-bandwidth faculties: spatial, musical, empathetic, and so on, each one of which, he says, “is like a superpower.” His call to action is that,

Even though it doesn’t seem feasible right now, I think we need to start thinking about how to design the humane medium with the technology that we want to have.8

In the prospective world that he imagines, ordinary people have become the magic poets of the air, “as imagination bodies forth / The forms of things unknown.”9 For visionaries like Alan Kay and Bret Victor, the dream of the new medium is to be a “fantasy amplifier”—a dynamic thought-space where we can be fully human, and indeed reinvent humanity.10 Perhaps, like Theseus, we “never may believe / these antic fables, nor these fairy toys.” But if we don’t start working on this now, Victor warns, the forces that do shape the new medium will not be concerned about our underutilized superpowers.

The Luddite who loves humankind would be forgiven for finding hope in a future where some form of amplified, cooperative reasoning has become as “common” as literacy. But if today’s computing machines are “inhumane” by design—especially for the purpose of “knowledge work”—what good can they possibly be for the humanities? It is not an idle question, I hope, for any project that would arrange to wed the two. We should not be persuaded that we love these “cages” by the mere fact that we have bought billions of them. If we are not “enthralled” to them, we must see them for what they are; we must, with Tolstoy, deny them any “non-existent merits,” whatever “the whole of the civilized world” may claim. Only when we choose with our own eyes, do we choose freely.

Although today’s computers are vastly superior to the “memex” that Vannevar Bush dared to dream of in 1945, we cannot kid ourselves that they are “technology that we want to have” as a working environment. For creative work in particular, we would never choose today’s screens over tomorrow’s sorcery, any more than Titania would choose a “monster” over her fairy king. They may be harmless enough in short sittings, but we would rightly “loathe” to look on them them after a lifetime in their gaze.11

And yet, for the nuptial night’s “abridgement” and “delights,” Theseus does choose the “rude mechanicals” over more sophisticated “devices.” The players are not “fitted” to the task, he is told. But he insists. “The best in this kind are but shadows,” he says, “and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend them.” Hippolyta’s snarky reply is: It must be your imagination then, and not theirs. Ultimately, all representations, from the oldest manuscript to the most far-out hologram, “are but shadows”; the real action is still within us. Reading, listening, and watching are at best creative acts—and at least, acts of recreation. These activities, when we choose them for ourselves, should “never harm."12

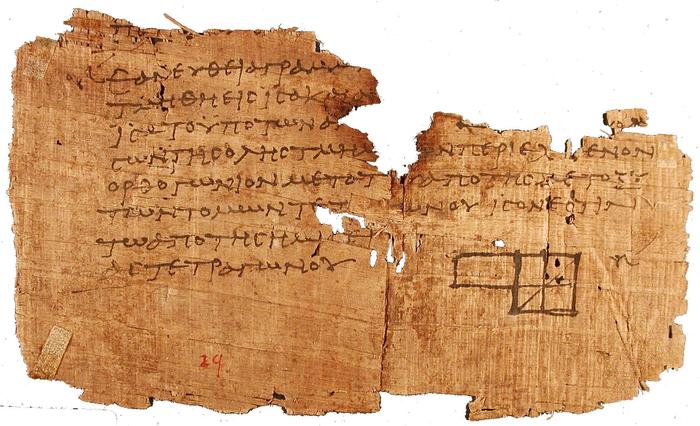

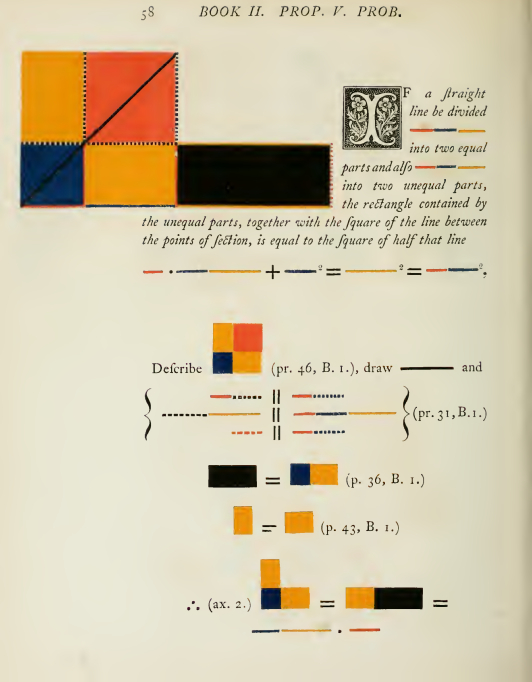

But the newlyweds don’t merely “amend” the show, they amplify it—with their responses—into something more than it was. If it makes sense to think ahead about what we’d do with media that we might have someday, we may also ask ourselves how to amplify the beloved creations of the past, using the medium that we have now. Forms can amplify themselves, by presenting the same idea in different ways, such as the “dumb shows,” that briefly summarize a play with narrative and pantomime. The effect is even more powerful when we “parallelize” the presentation by engaging several abilities at once. Childrens books operate this way, especially when read aloud. Figure 5 presents two examples of “old” books being amplified to engage more of the reader’s mind. Over two thousand years after Euclid wrote his treatise on geometry, Oliver Byrne (“the Matisse of mathematics”) created a visual language to augment Euclid’s symbolic one. Byrne believed that this multi-faceted approach represented a great advance in education, “for it would teach the people how to think, and not what to think.” Byrne is also interested in the special benefits of parallel presentation:

In oral demonstrations, we gain with colours this important advantage, the eye and the ear can be addressed at the same moment 13

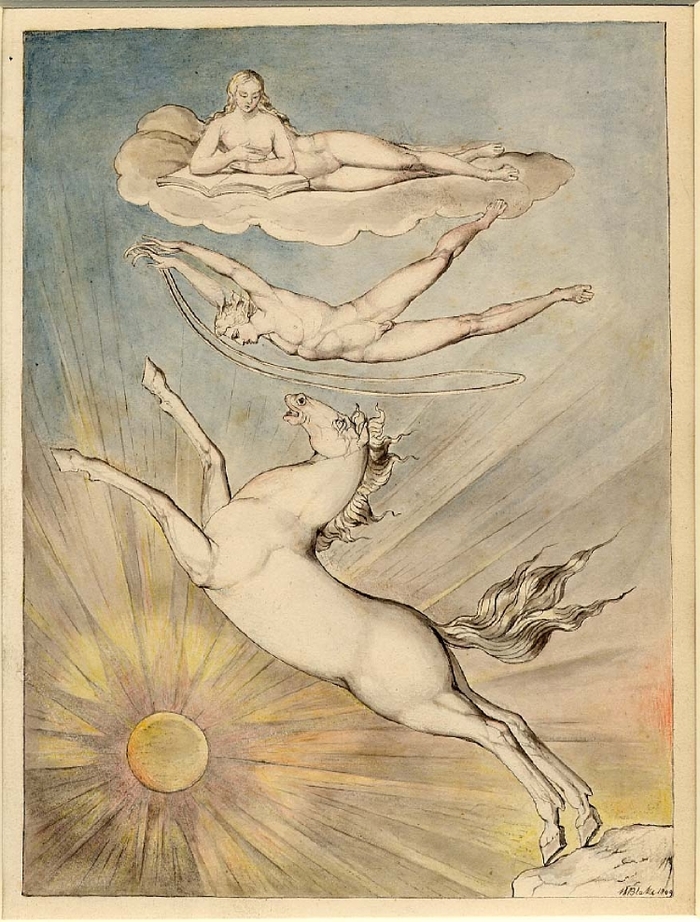

Note that in such a setting, no appeal to symbolic manipulation is necessary at all. For those people who would always see the page of symbols as “Greek to me,” the value added by these alternative channels cannot be overstated.14 Literature can also speak to new audiences when liberated in this way. To take just one example, William Blake (another multimedia master) applied his innovations in printmaking to “illuminate” numerous subjects, including the Bible, Shakespeare, and later, his own fiercely original writings.15

Amplification is also about space: making more ample, more voluminous. Consider the challenge faced by the editors of the MLA “New Variorum Shakespeare,” which aims to encompass four centuries of critical responses in addition to a readable text of the works. They are cornered at every turn by the space constraints of a printed volume.16 In the unlimited space of the virtual world, the “complete Shakespeare” can be just that—a new, almost “unthinkable” kind of place that is at once a Folger library, a Boydell gallery, a Globe theater, and a Shakespeare garden.

This amplification complements the “digitization” projects taking place at many institutions, including that priceless foundation, the Internet Archive. Long live the Internet Archive! To scan the world’s public collections for all to access is a great, essential service to humanity. But they are nothing new. Digitizations—no matter how well done—“are but shadows” of those treasures, shallow projections that retain all the limitations of the originals, even while they sacrifice their tactile presence. General archives can only operate at a large scale by viewing each work as a unit of some type. From that viewpoint, books, images, films, and so on, are all the same.

Whereas, the kind of amplification that I propose is a creative collaboration with a specific work or body of work, giving it a chance to reshape itself in a new space. Admittedly, it is a process that does not scale. To give new homes to the creators of old, we have to make them one by one.

But it is “feasible” to start this work now. In some respect, the new world already exists, though “small and undistinguishable / Like far-off mountains turned into clouds.” We already talk about virtual places; we already agree that there is—at least notionally—a place called “hyperspace.” With time, that so-called “place” will grow more literal.

3.4 why ongoing

No, Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change:

Thy pyramids built up with newer might

To me are nothing novel, nothing strange;

They are but dressings of a former sight.

In late December of 1598, a London playhouse called “The Theatre” was dismantled. The lease on the site was up, but the timber was still sturdy. In the spring of 1599, the remains of “The Theatre” were taken, piece by piece, across the river Thames and reassembled—“built up with newer might,” you could say—into “The Globe.” That theater caught fire from a cannon accident during a 1613 performance of Henry VIII and burned to the ground. It was rebuilt again on the same site the following year. That theater (the “Reconstructed Globe”) remained standing until 1644, when it was demolished by the Puritans.

When Sam Wanamaker set out to re-reconstruct the Globe theater at the end of the twentieth century, the challenge was not building a theater, so much as it was having any clue what to rebuild. Wanamaker, an American actor and director who moved to England after being blacklisted in the early 1950’s, “had sought traces of the original theatre and was astonished to find only a blackened plaque on an unused brewery.”17 There were no surviving plans, if there had been any plans in the first place. The design of “Shakespeare’s Globe” (as the current incarnation is called) was pieced together from “printed panoramas,” “written accounts” and, literally, “suggestive descriptions included in the plays themselves"—including the “wooden O” passage in Henry V.18 So by alluding to his beloved venue in his own dramas, Shakespeare actually had a hand in the rebuilding of the Globe four centuries later! Sadly, Wanamaker did not live to see it in action.

Shakespeare was obsessed with Time—or at least, with its ravages. This obsession is most obvious in the sonnets, an intimate set of poems where Shakespeare speaks not as a character but (we may imagine) as himself. He is writing to an “unthrifty” (and unidentified) young man whom he loves, telling him that, when it comes to “wasteful” and “devouring Time,” you have two main lines of defense. The first one is to “breed another thee”, for “Then what could death do, if thou shouldst depart / Leaving thee living in posterity?” Of course, this didn’t work out so well for Shakespeare himself, whose last living grandchild, Elizabeth Barnard, died childless at age sixty-one, ending the poet’s line.

The other way to beat Death and Time, says the poet, is poetry. Sonnet 18 concludes,

Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou growest:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

This prediction has borne out much better for the Bard. Poetry travels through speaking and writing—so long as men can breathe or eyes can see—and this redundancy makes it all the more durable. It can even “live in thy memory,” as Hamlet says, where it is as about as unmediated any representation can be. Words are immortal—at least in the abstract—and thanks to alphabets, language is easily encoded for perfect replication in perpetuity. And yet something is lost, as society changes. Even if we could hear the exact same words that were spoken at the old Globe theater, the world that gave them their meaning has moved on. Many passages of Shakespeare sound “like a foreign language” to English speakers today, even when the differences are merely superficial.

Like language itself, digital media seems to offer this fountain of youth to anything that can be scanned; and likewise, it does not quite deliver on that promise. Even in the discrete, disembodied form of code, information is not immune to decay. We may preserve the same bits unchanged for a hundred years, but the processing environment will change, rendering them unusable. Systems evolve, formats become obsolete, and left to its own, the knowledge that we represent today will be inaccessible in a century. If you’re writing your will, the optimistic choice is paper.

As such, it is a death sentence to see anything that you care about as a collection of bits. So yes, willshake is a “software project,” in the sense that it produces a software product. But the software product is disposable. And the thing that matters in a hundred years “won’t be software,” anyway.7 The real product is a form of inquiry—and a process of destruction and renewal. I’ve scrapped and rebuilt willshake countless times already, and if I ever vow not to light the cannon again, I trust that some good person will.

Whilst this machine is to him,

Gavin Cannizzaro

Footnotes:

“West Side Story, § Critical Reaction”. The quote is cited from the New York Daily News of September 27, 1957.

“Orson Welles Shakespeare Collection” at the Internet Archive

It is still #2 on Google for “Shakespeare,” Wikipedia having passed it at some point. But note that Wikipedia’s article is about Shakespeare—it does not host the works.

From the preface to the Johnson-Steevens 1765 edition. (at Project Gutenberg)

As of this writing, three of the top five Google results for the term “no fear” (by itself!) are for “No Fear Shakespeare” (referring to their print editions); while “No Sweat Shakespeare” is one of the higher-ranking online study aids.

On the “huge change in outlook for our planet” represented by the printing press, see Alan Kay, “Normal Considered Harmful” (video). On the complete invisibility of the next century’s most important thing, see Bret Victor, “An Ill-Advised Personal Note about ‘Media for Thinking the Unthinkable’,” May 2013.

“The Humane Representation of Thought” on Vimeo. Highly recommended.

See Howard Rheingold, “The Birth of the Fantasy Amplifier,” Tools for Thought, 1985. Also, Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human.

Although out of scope here, I would urge the same skepticism towards computer-based educational tools, when the recommendations are not coming from educators; the same considerations also apply to those products just entering the marketplace, such as the “VR goggles” shown in Figure 3, or the “augmented reality” systems being prototyped.

“Fiction does its work,” says John Gardner, “by creating a dream in the reader’s mind.” This can be extended from reading and listening to experience itself. “We actually are creatures who, from moment to moment, are in our own hallucination,” as Alan Kay puts it. For more about what he calls “the ghost” and “the dream,” see his talk “The Future Doesn’t Have To Be Incremental.”

(emphasis mine) Byrne’s Euclid at the Internet Archive. The reception of the work is discussed in “Byrne’s Euclid: Geometry Understood via Color-coded Diagrams” from Oliver Byrne: The Matisse of Mathematics by Susan M. Hawes and Sid Kolpas

Extensions of this approach into a dynamic, interactive medium are easily imagined for math and sciences, though they would be subject to the poor input facilities of today’s models. The closest thing I found for Euclid was a twenty-year-old applet that no longer works.

Indeed, Blake’s prophetic poems are inseparable from their accompanying plates; they are fully creations of a new medium.

The 2003 edition does include a hyperlinked PDF version, and gives a nod to further potential in this area. But to me, it reads ike a rationale for the fundamental migration into hyperspace as being outside their scope of work.

“Sam Wanamaker,” Wikipedia, quoting Edward Chaney, “Sam Wanamaker’s Global Legacy”, Salisbury Review, June 1995, pp. 38–40.

Henry 5, Prologue (at willshake). See “Rebuilding the Globe,” from the official web site of The Shakespeare’s Globe Trust, copyright 2016.